A few weeks ago, the American Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy claimed that use of the pain medication Tylenol in pregnant women is linked to autistic children – an absurd claim without any scientific evidence to its name. But this fits into a larger pattern of hysteria about and against people with autism, including blaming the mothers for something allegedly being “wrong” with their autistic children.

While the specifics of this particular hysteria are new, the general pattern is not – as I shall show, it fits into the “changeling” narratives where “apparently healthy” infants were switched by spirits with entities that appeared to be “misbehaving” or disabled in some manner.

Content warning: Ableism, child abuse, and infanticide.

The Grass Devil

A long time ago, a maid lived at Siegburg who was a serf of the monastery.[1] She gave birth to a little boy before she was led to the altar by a man. She suffered a harsh punishment for becoming a mother in such a sinful manner. For when her child was a few months old and it was the time for the hay harvest, she took the little one with her to work when she was called up to do her labors on the meadow.[2] And when she was preoccupied with turning grass over,[3] she put him down on a half-dry heap. She was working at a stone throw’s distance in this manner when he started to cry pitifully. Then she went there in order to breastfeed him. But even though the child had been calm and content until now, she was no longer able to satiate him.

And he seemed to be completely changed, for he cried nonstop day and night and partook of so much nourishment that ten children might have been satiated by it otherwise. He furthermore caused a lot of hardship to the mother because of his overwhelming filthiness. During all this, he did not grow, did not gain any weight, but stayed like he was, which bothered the mother greatly and which she tearfully lamented to clever women.

Then she heard from everyone that the child had been bewitched, and that there would be no other way of curing him than to bring him to St. Cyriacus at Overrath, weigh him on the scales of Cyriacus, and give him something to drink from Cyriacus’ Well.[4] This was the custom in those times which is still adhered to in our days. Children who do not grow and thrive will be weighed on the great scales of St. Cyriacus, and people are then convinced that, by the ninth day after this, the fate of the weighed child will be decided to be either death or recovery.

The sorrowful mother saw no other path to saving her child, and thus went on the way, carrying her child, until she had reached the Acher bridge.[5] Then the little glutton seemed to be so heavy to her that she was unable to proceed further, and, gasping for breath and drenched in sweat, leaned against the guardrails of the bridge.

At this moment, a traveling mendicant monk came along the path, spoke to the exhausted woman in a friendly manner, bid her greetings, and said: “Well, my dear woman, what kind of horrible creature do you have on your back? That one will push you into the ground if you do not let it go.”

“It is my dear child”, replied the sorrowful mother, “who won’t grow and prosper. Thus, I am going to the scales of St. Cyriacus in order to weigh him, as the old women have told me. Then hopefully the poor little worm will get better again, for it seems that he has been cursed by an evil witch.”

“What witch?” exclaimed the wise padre. “There is no enchantment upon this brat. End your cuddling which is horribly wasted on this burden. Instead, throw it into the water, for this is not your child and no child of any human, but an actual grass devil! It is an old dwarf which has been switched with your child. Throw the trickster down into the water, for the love of your true child and your own salvation!”

“No,” answered the frightened mother, “how could I do such a terrible thing to my own flesh and blood? I have carried the poor little worm, stilled it, and raised it, and know that it is my child. But when I went out with other women in order to make hay on the abbot’s meadow and put the child on a dried heap of grass, an evil eye passed over him. For then he started to cry like he has never done it before, and from that moment on he seems to have changed for the worst.”

“At that moment, the malicious kobolds[6] from the Wolsberg[7] moment stole your child and put that creature at the same spot,” replied the monk. “They take care of your child within the mountain, like they have done with quite a few other stolen children. But if you throw this changeling into the water, then they must bring your child back within the hour. Then you will find it at home in the crib, healthy and hale, well-grown like other children – and not like this creature, which will suck you into the grave if you keep him for any longer.”

The devout monk said this with such conviction that the woman was barely able to stay on her feet. Then, in a whirlwind of fear, dread, and love, half will-less and subconsciously, she let the child drop over the guardrails. Then the little creature screamed horribly, and down in the water a ruckus arose as if the river was about to boil, and a roar as if bears and lindwurms[8] were moving around in it. Then the mother realized that the monk had spoken the truth. Driven by fear and hope, she hurried back home where she indeed found her child in the crib as the monk had predicted it – healthy and hale, and well-grown like other children.

[1] This refers to Michaelsberg Abbey, a Benedictine monastery founded in 1064 by Anno II, the archbishop of Cologne. It was finally dissolved in 2011 when the number of monks serving in it became too small.

[2] As a serf, she had to do corvée labors for her liege lord – in this case, the monastery.

[3] The goal was to dry the grass so that it could be collected as hay.

[4] This likely refers to a chapel that used to be located in what is now modern-day Cyriax, a district of Overrath. Both are named after Cyriacus, a Roman noble who converted to Christianity and was subsequently martyred in 303 during the Diocletianic Persecution. A monastery in this village was secularized in 1803, and its buildings were subsequently used for agricultural purposes. The whole journey would have covered a distance of more than 17 km.

[5] Most likely a bridge over the river Agger. The most logical location of this bridge would have been at Wahlscheid, a district of Lohmar.

[6] As a reminder, “kobold” is a generic term for “small, mischievous spirit” in German, similar to the British “goblin”.

[7] The Wolsberg is a hill located within the Wolsburg district of Siegburg.

[8] Another name for dragons, usually of a wingless and serpentine variety.

Commentary: Here we see the basics of the changeling narrative. First, it is the mother who is blamed for getting a changeling. The story claims that this is a direct consequence for having a child out of wedlock, without presenting any evidence for this. And then it is the mother’s inattention for allowing the spirits to switch the child, even though this was hardly a moral failing on her part – she simply did not have any support group which could have provided childcare while she was working, and was too poor to hire anyone (and her liege lords obviously did not care about this state of affairs, either).

The rest of the story is even more insidious: “This misbehaving, underdeveloped creature is not the woman’s real child – so the solution is to get rid of it in a likely-lethal way so that the real child (which is well-behaved and healthy) will be brought back by the spirits!”

I have to wonder: How many mothers of centuries past, upon hearing such tales, convinced themselves that their infant child was not their real child because it has some mental or physical disability? Or perhaps she was suffering from (obviously undiagnosed) postpartum depression, and used this narrative as an explanation for her moods. Or perhaps she was resentful about her pregnancy and new motherhood in general – after all, this was during a time when women barely had any control over their fertility other than in the most crude ways. No matter what the mother’s precise circumstances were, the changeling narrative was a useful justification for infanticide.

As for the rest of the community, rural populations who frequently experienced famine and starvation were often rather more enthusiastic supporters of eugenics than the laws of the land – or church doctrine. Their goal was to have healthy, grown-up men and women who would support their parents in old age, not people with disabilities who would consume resources but who would be unable to contribute as much as healthy people. Thus, changeling narratives were useful as a justification for infanticide for the rest of the community as well.

I have little doubt that a lot of children died because of such stories.

The Changeling. Premenk

(Haupt and Schmaler II, p. 267. Oral account.)[1]

Until the time when a child has reached an age of six weeks, there must always be a person nearby. For otherwise, an old woman might come from the mountains or from the forest and replace the infant with a changeling. This changeling is misshapen, as well as weak in body and mind. At the very least, people should place a hymn book next to the head of the child before they leave the chamber.

But if this misfortune has occurred due to neglect, then it is good if you realize this early on. Then you need only fashion a rod from the branches of the silver birch, and thoroughly beat the changeling with it.

When it screams, the old woman will come and have the switched child with her. She will give the child back, and leave with the creature. However, you must let her go on her way, and in no case berate or admonish her. For otherwise, you will be stuck with the changeling.

Source: Haupt, K. Sagenbuch der Lausitz. Erster Theil: Das Geisterreich. 1865, p.69.

[1] This refers to the second volume of “Volkslieder der Wenden in der Ober- und Nieder-Lausitz” by Leopold Haupt and Johann Ernst Schmaler. The relevant text – a slightly abbreviated entry in encyclopaedic form – can be found here.

Commentary: Again, the appearance of a changeling is blamed on negligence, although the mother is not explicitly singled out as being at fault for this situation. And again, the suggested solution is violence against the apparent infant. The true nature of the “old woman” is unclear, although she obviously is a spirit of some kind. But we never learn why she would switch out children, nor why she would bring them back if the changeling is abused.

Driving a Changeling Away By Beating Them With A Blunt Broom

The people on a large estate were busy with threshing grain. A new mother wanted to help with the work. She thus left her small child lying in the crib, and went into the barn in order to help with the threshing. When she came back to the chamber, her child was gone, and an ugly thing was lying in the crib which was extremely foolish[1] and which cried without pause. The child had thus been switched and a changeling had been put into the crib.

The women in the neighborhood thus gave her the advice that she should beat it with a blunt broom until she received her own child back. And indeed, she did so, and hit it so pitylessly that the changeling writhed horribly and screamed. But she did not stop, and soon bloody streaks were visible on its body. Then suddenly the door was ripped open and her own child was pushed in. The child was just as beaten up as the changeling, which was now suddenly gone.

(Oral tale from the cook Anna Cl. from Langenau at Katscher.[2] 1906.)

Source: Kühnau, R. Schlesische Sagen. Zweiter Theil: Elben- Dämonen und Teufelsagen. 1865, p. 158.

[1] The German term used was “Strudelkopf” (“Strudel head”, with “Strudel” representing a type of German pastry). I initially took this to be a comment on the appearance of the changeling, but it turned out that this used to be a metaphor for “an extremely foolish person”).

[2] Langenau was incorporated into Katscher, now the town of Kietrz in the Opole Voivodeship of Poland.

Commentary: Here the violence gets even more intense, with the mother continuing to beat the apparent infant until it is bloody all over. Whatever entity switched the changeling did obviously not appreciate this kind of treatment, as they returned the actual infant in a similar sorry state.

Of course, this narrative could also be used to cover up child abuse: “My child was switched by a changeling, so I had to beat up the changeling in order to get my real child back! And the spirits returned my child in this sorry state!” In other words, the mother did not just beat their own child until they were bloody in a fit of rage – it was the spirits’ fault!

Changeling Beaten By A Rod

(Prätor. Weltbeschreibung I. 365. 366.)[1]

The following true story occurred in the year 1580: A noteworthy nobleman lived near Breslau[2] who needed a lot of grass to be cut and turned into hay in the summer, and his subjects had to do these labors for him. Among these there was a new mother who had rested in bed after having given birth for a mere eight days. As she saw that this was the will of the noble and she was unable to refuse, she took her child with her, put the child on a small heap of grass, went away and assisted with the haymaking.

When she had worked for a good while and went to breastfeed her child, she looked at the child, screamed loudly, threw her hands up in horror, and wailed vehemently that this was not her child since it greedily sucked from her milk and howled in such an inhuman manner which she was not used to from her own child.

Despite everything, she kept it with her for many days, and it acted in such a horrible manner that the poor woman was close to ruin. She complained about this to the noble, and he said to her: “Woman, if you believe that this is not your child, so go and carry it to the meadow where you have put the previous child. There you should beat it heavily with a rod, and then you shall see strange things.”

The woman followed the advice of the noble. She went outside and beat the changeling with a rod so that it screamed loudly. Then the Devil brought her stolen child and spoke: “There you have it!” And with these words, he took his own child away.

This story is well known to both young and old in the same area in and near Breslau.

Source: Grimm, J. and W. Deutsche Sagen, Band 1. 1816, p. 144f.

[1] “Anthropodemus Plutonicus, das ist, Eine Neue Weltbeschreibung”, published in 1666 by Johannes Praetorius. The relevant section can be found here.

[2] Now Wrocław in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship.

Commentary: Beyond providing us a glimpse into the harsh labor conditions of 16th century Silesia, where women were expected to do hard work soon after giving birth (which was a widespread state of affairs – generally, only women from the upper classes or who lived in developed countries were able to rest for multiple weeks before resuming their usual daily work), this story implies that a changeling comes directly from the Devil – and like all spawn of Hell, it thus deserves no pity or consideration.

Which again fits into the larger, horrible narratives about changelings: If an infant does not “function to specifications” – that is to say, if they are too loud, too fussy, or if they have some kind of developmental disorders – then they are not a real human infant, and not the real offspring of the mother. Instead, they are an otherworldly creature that must be abused until the “proper” state of affairs is restored.

In other words, such tales are encouragement for child abuse – and while the folkloric changeling tales may be gone, similar modern narratives have taken their place. I’ve mentioned the recent anti-autism hysteria, but there are many others. How many LGTB children have been rejected by their parents for not fitting into their parents’ narrow world views – or being forced into “conversion therapy” (another form of child abuse which in its own way is no less cruel than the beatings that were portrayed in these tales)?

Folklore is not a thing of the past. It lives on – for good or ill. And we need to be aware of the latter, and how it shapes our politics, societies, and very lives.

Further reading: My new wiki has several further tales featuring changelings. In particular, “Witches and Trudes” make the nature of changelings as Devil-spawn explicit. It also claims that if women use magic to ease the pain of childbirth, the resulting children will have a propensity of evil – another parallel to the modern hysteria about Tylenol.

Note: This article has been posted on the Fediverse via the WordPress ActivityPub plugin. You can share and comment on this article by searching for the article’s URL in the search box of your Fediverse instance.

@juergen_hubert Here is a *really wholesome* story about autistic "changelings" (three stories in one, really) https://roachpatrol.tumblr.com/post/161863637967/heres-a-story-about-changelings-mary-was-a

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

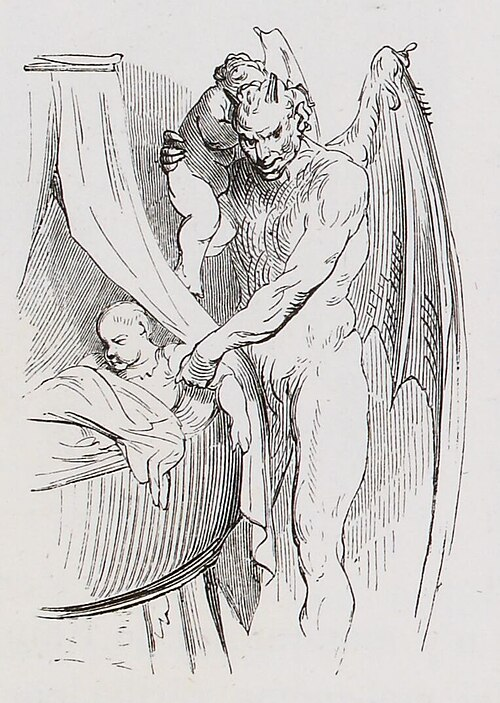

@juergen_hubert #alt4you Engraving of a man-sized, horned, and bat-winged devil holding one infant as it plucks another from a crib.

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile